a doctor who gets it

One of the first people I spoke to on my book tour last spring was Mara Gordon, who writes for NPR. Gordon is a practicing primary care doctor in Philadelphia, and as we talked, I found she had a refreshing relationship with being a doctor, and how she saw her role in relation to her patients. She also seemed to have a lot of understanding about all the ways patients’ needs are not being met in America. Gordon even wrote an essay in 2024 about her specific challenges in being an anti-diet doctor in the age of GLP-1s being prescribed for weight loss.

I hear often from readers about their frustration and dismay with doctors, especially with regard to body weight, which many doctors still put at the center of patients' health picture. While many doctors are responsive to patients’ changing needs, dismissive and judgmental interactions are frighteningly common. (And, unfortunately, primary care doctors are often just the spear tip of an inept, broken, predatory healthcare system). With a closed-door situation like doctors’ appointments, I often find myself frustrated, because there’s nowhere to turn for information on how these interaction should go. Is he allowed to just say that? We all end up asking ourselves. Shouldn’t he be asking fewer questions? Shouldn’t he be asking more questions?

But Gordon is the unique doctor with clarity about this general problem, and I wanted to ask her for more of her insights on what is going awry. We spoke a lot about GLP-1s, the current axis point on which a lot of health discussion currently turns. She has an amazing perspective on what a functional doctor-patient-relationship looks like, as well as whether it’s possible. (It is possible, and it may be why your doctor is always running late.)

She generously spoke to me after a long shift, with her young son waiting in the wings to show her his new light-up sneakers. She’s A Beast thanks him for his patience.

I got the impression when we spoke last spring that you had notes for people in your profession, and the way that doctor/patient interactions go.

I see medicine and science as a tool for social issues. I've ended up in Philadelphia most of my adult life, but I sort had this dream of being a small time, small town doctor, having these long term, trusted relationships. I have that with some of my patients, particularly the ones I've been in my current job since 2019. I feel like I know them, their kids, their grandkids. But not everyone does, and that’s a huge cause of the disconnect.

As a patient, I could offer that I've changed jobs a lot. Changed insurance a lot. At a lot of points I would not have had the opportunity to see the same doctor more than once or twice, maybe, if I were on the ball in terms of appointments.

And it's normal, right? The idea that you live in the same small town for your whole life is just not what American life is like in 2025. People are more mobile, people switch jobs a lot. Their insurance changes a lot. Doctors leave practice, too. There's a lot working against us.

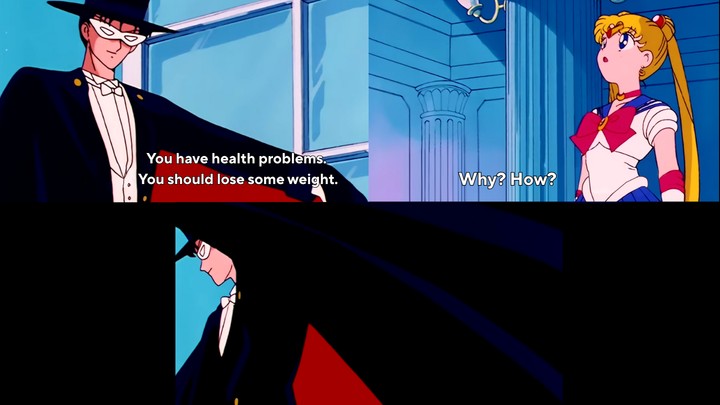

I hear from a lot of readers who have an above-normal BMI—quote-unquote above-normal, quote-unquote BMI. They’ll go to the doctor with health issues. The doctor will say, maybe you should try losing weight. And even if this patient is sort of game to do that, the patient will say, how do I do that, and the doctor will say, by eating less, and they’ll just flourish out of the room. (This was pre-GLP-1s as a weight loss tool; now it seems like everyone is eager to smash the GLP-1 button instead.) It’s like they revolve a lot of their care, or lack of care, around this one metric, but then offer little to no help to put those pieces together. What notes would you give to either person on either side of this interaction?

Very early on in my training, like as a medical student, it felt like it was my job to convince somebody to go on birth control when they didn't want to be in birth control, or to convince somebody to quit smoking, when they weren't ready to quit smoking. (Smoking is a little bit different from birth control and BMI, pretty clearly established to have a lot of harms.) Now, I describe myself as an anti-diet doctor, which has, for me, a very simple definition: I don't yell at my patients to lose weight. People were coming to me asking for GLP-1s, and I was like, I'm not an obesity doctor. I wrote an essay for NPR in 2024 about being a body positive doctor in the age of Ozempic. I think people think that they're going to fix so many complicated negative thoughts wrapped up in their bodies, size, and body image, and lo and behold, the medications do not solve that.

On the other hand—that doesn't mean I'm opposed to ever discussing intentional weight loss with my patients. When somebody comes to me asking about GLP-1s my first question is, what's your goal? What have you heard? I think a lot of doctors don't ask that question because our visits are so short. It's not that I magically have more time than everybody else. I just always run late. But pausing to help the patient define what their goals are is really useful, because GLP-1s are really, really good at a narrow range of what we call indications: lowering your hemoglobin A1C, which is a measure of blood sugar. Reducing inflammation in the liver related to metabolic dysfunction and fatty tissue in the liver. They are really good at protecting your heart, your kidneys. They do not solve body dysmorphia. That's not an indication. They do not work for that.

We can't have bots here.

Let's see some ID. (Just your real email, please.)