Why can’t a human body go to Mars? I’m glad you asked

A few days ago, Elon Musk was, once again, posting on Twitter about sending people to Mars. In this case, he said, “The first Starships to Mars will launch in 2 years when the next Earth-Mars transfer window opens.”

I haven’t given “people on Mars” a lot of serious thought. I try to preserve my time and energy for more realistic and consequential endeavors. But this is, broadly interpreted, a newsletter about body science and health, often as those things intersect with politics and the future. As a publication, we also cultivate a healthy skepticism of Elon, who is not only a rich kid who bumbles around with Daddy’s money, but is increasingly under the influence of a lot of drugs, and besides is profoundly, irredeemably gross and weird. Lately, Elon is trying to bluster about the big bright future of distant space travel as a way of currying public favor for Donald Trump’s campaign.

The last time I spent any time on this subject was in 2013, when I wrote about the extremely dubious Mars One “mission” that tricked some 200,000 people into paying $40 to fill out an application for a chance to be one of its lucky workaday astronauts. Mars One was thoroughly debunked on several fronts, including that its proposed space base would suffocate its inhabitants within 68 days, and went bankrupt in 2019. But you and I would be forgiven for thinking this is a near-term possibility, with people like Elon throwing around timelines of “the year after next” and presumably raising money based on these incredibly self-assured statements.

Because of these things, I thought it’d be interesting to take a little detour into what stands between we humans and a Mars colony, biologically. People are in space all the time, in the International Space Station. If it were a good idea to just leave this planet behind and take to space (which it isn’t), why couldn’t we just do it?

I didn’t have to look far for answers. I always thought there were the usual space travel issues, just more, since Mars is distant: loneliness; muscle loss (behold the Interim Resistive Exercise Device!); difficult supply logistics with food and stuff. But in the late '90s, scientists started studying the challenges of a Mars-type mission in earnest. And boy, did they find some challenges.

They knew there was “cosmic radiation” out there, about 100 times stronger than what we get on Earth. Earth’s magnetosphere protects us from a lot of it, and the ISS orbits close enough to Earth that it’s still blocked from this radiation. Mars has no such magnetosphere, so not only is its surface receiving the constant full firehose of cosmic radiation, it also gets blasted with surges of radiation from the sun. It might cause more and faster cancer, the scientists said, but we should look into it more.

And so they did. And today, we have a much clearer and, shall we say, more vivid understanding of what exactly stands in the way of sending humans to Mars.

The biggest problem is still the cosmic radiation. But now we have gained an understanding of what exactly the cosmic radiation does.

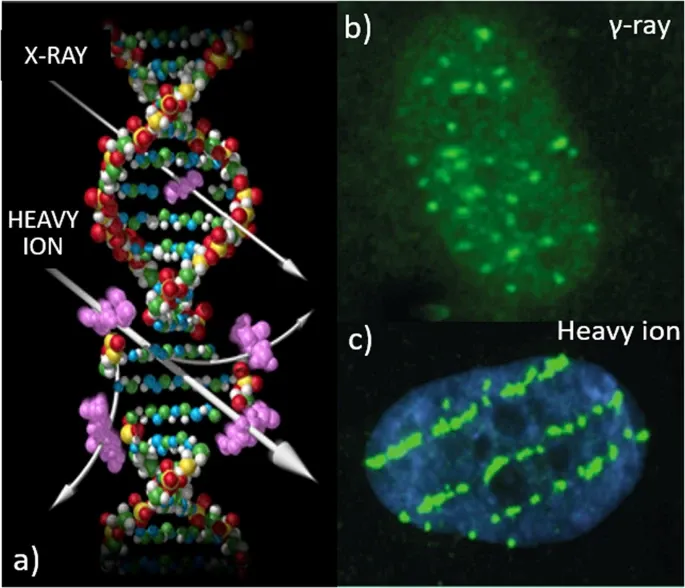

We are familiar with radiation in the form of X-rays, which are overall safe in small doses that let doctors see inside your body. They aren’t amazing for us and very, very slightly raise our risk of cancer, but benefits outweigh the costs by a lot.

Cosmic radiation is like X-rays on steroids. It’s extremely high-energy particles that “produce complex DNA lesions with clustered double-stranded and single-stranded DNA breaks that are difficult to repair.” One study found “persistently high levels of oxidative damage”, the precursor to plenty of problems including cancer, in mice exposed to similar radiation after one year. As one 2020 Nature paper notes, we don’t even actually know if this radiation would produce tumors like the ones we are used to dealing with here on Earth, or another type entirely. Yes, you read that right: a potential brand new form of space cancer.

Cancer isn’t even the only problem. Radiation can also cause “cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, cataracts, digestive and endocrine disorders, immune system decrements, and respiratory dysfunction.” Our forms of radiation here on Earth don’t really affect our central nervous systems, but cosmic radiation might, increasing the risks of “Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or accelerated aging.” We have known for about 15 years that spaceflight does cause various problems in astronauts’ vision. Missions have tried to provide the astronauts with contacts to help protect their eyes, but contacts do nothing for symptoms like the flattening of the eyeballs, which science is still working to understand.

The really funny thing about all of these still-unknowns is that it’s not super practical, or nice, to send people or things up there to see just how fast they get cancer, or how quickly their spines shrivel up like grapes, or if they all make it back safe and then all die of heart attacks within the next calendar year. And we don’t even have a great way of simulating the effects of cosmic radiation here on Earth. There is one lab, the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory in Long Island, that can produce the right types of ions that simulate what we might go through in space. Who wants to get in first?

The practical-minded part of me imagines there must be a way of blocking the radiation. But to block even the relatively weak X-rays, we have to wear a giant lead apron. What will block cosmic radiation? A six-foot-thick thorium wall? We don’t know. We have no idea. Part of why I’m writing this is many pieces I’ve now read about the challenges of going to Mars focus mostly on, like, bone loss, or the planet’s very small dust particles. I say let’s not ignore the fact that we’d be (not-that-slowly!) drowning in a sea of highly charged ions that would be knocking DNA fragments in our bodies loose like wrecking balls. I’d in fact like to hear more about how, not long after entering space, we’d pretty quickly waste away and die.

Well, we don’t have to live on Mars, you might be saying. What if we just want to make a quick trip—what’s the minimum length of time to go there and back? I’m glad you asked, because it’s almost two years.

I love science as much as the next guy; I know it always finds a way; I never say never. I think exploration of the universe is all well and good. But when a doped-up man says we’re packing up and shipping off to Mars in the next two years, I say, I’ll have what he’s having.

Eat

~Liftcord Pick of the Week: There was a lovely discussion around what to expect from a personal trainer with advice from seasoned Beasties earlier this week! If you search “personal trainer for the first time” in the #general-chat channel it’ll come up. Also, this very thorough feature on Prince.~

Delightful behind-the-scenes video of Olympic rugby star and medalist Ilona Maher’s Sports Illustrated photoshoot.

Time for people to stop attributing to “core strength” what is actually “insane lats and shoulder stability.”

Since Taylor Swift endorsed Kamala Harris, it’s a nice time to revisit how strength training helped her perform the marathon Eras tour show.

Drink

Doctors’ latest solution to no one liking the BMI is “the body roundness index”, which relates weight and a person’s waist circumference. This does not really feel new, as waist measurements as a proxy for health have been around for some time. It also doesn’t feel like this is going to make anyone who was upset about BMI any happier. For some reason, the mental image this brings up for me is a doctor trying to measure the circumference of Violet Beauregarde from Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory as she turns into a big blueberry, and shaking his head in disappointment. Do with that what you will. (The way Gene Wilder says “Wrong!” in this clip, my god, what a legend.)

I know the impulse to listen to Kate Hudson and Kim Kardashian on medical matters is overwhelming, but you don’t need spontaneous “full-body scans.” (DEXA scans: also a waste of money, in most cases.)

It must have been an interesting game of Telephone that produced this Air Mail article on eating enough protein.

Rest

Someone knows something about why Ralph Nader’s favorite pen, the Paper Mate Flair, is worse now than it was when he first started using it in the '70s. (Paper Mate says it hasn’t changed, and I don’t believe them.)

Came across this story on Reddit from a guy who lived an entire imagined life in an injury-related blackout (or so he claims; great story, either way) and it’s from this thread of “glitches in the Matrix,” mostly eerie but good stories.

It’s the 50-year anniversary of The Power Broker. Read it, if you haven’t!

I have no relationship with Penzey’s Spices—they didn’t come to the Albany area until I was an adult—but it’s funny to see any brand tell off conservatives.

That’s all for this week! I love you for reading, thank you, let’s go—

Member discussion