Collagen sits on a throne of lies

ASK A SWOLE WOMAN

This is the paid Sunday Ask A Swole Woman edition ofShe’s a Beast, a newsletter about being strong mentally/emotionally/physically.

The Question

I know you don’t write about supplements that much. But what do you think of collagen? Is it any good? What’s the difference between collagen that has protein and, say, protein powder? Thanks love your newsletter! -Emily

The Answer

I wish I could remember where I first saw the collagen diet that turned out to be the suspected cause of dozens of deaths in the 70s. I couldn’t believe I’d never heard about it before. A diet product was suspected of killing a lot of people, and it’s not something we hear about constantly? Yes and yes, it turns out. But I am getting ahead of myself.

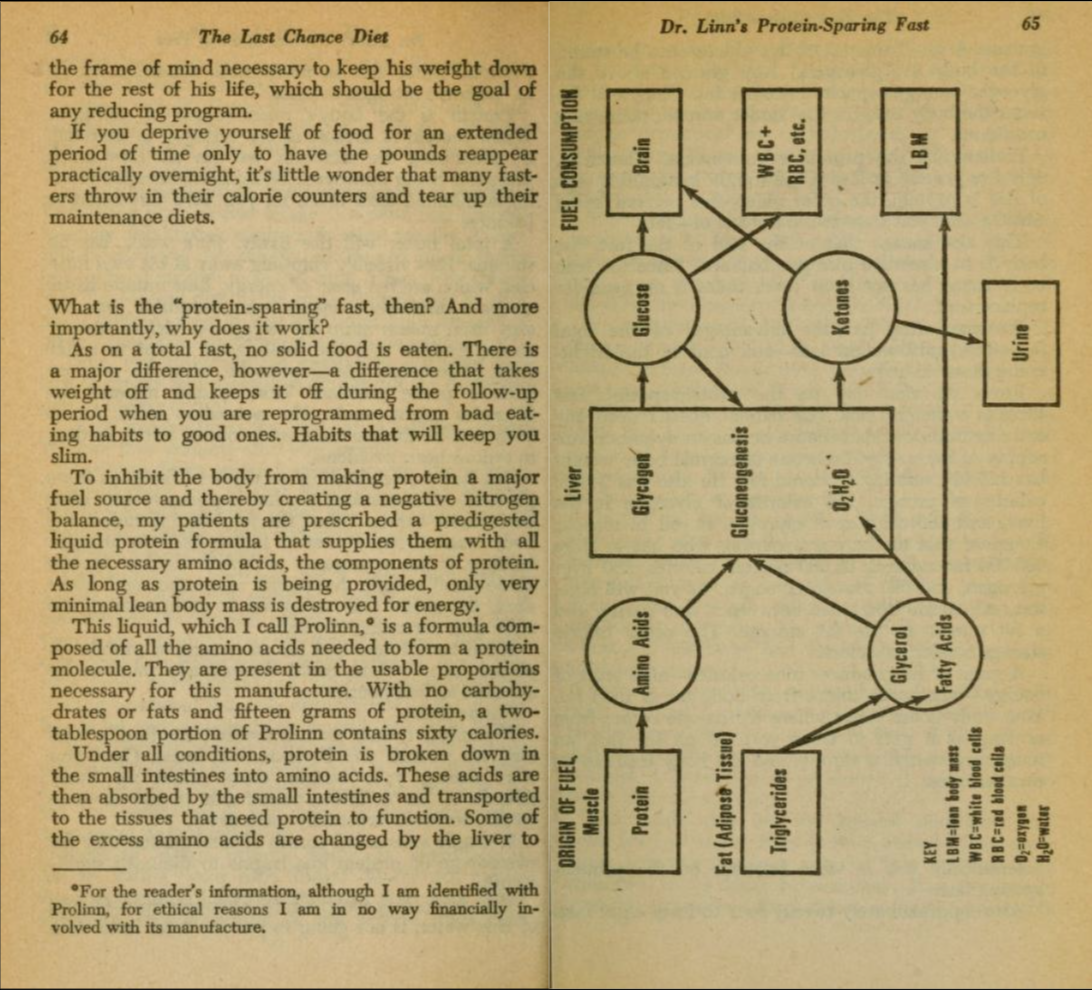

Osteopath Dr. Robert Linn’s The Last Chance Diet was a book published on January 1, 1976, and it describes a “protein-sparing fasting” diet. Linn wrote about a study that showed that, once bodies run through all their glucose for energy, the body started to break down fats into free fatty acids for fuel, and ketones, which “the brain can use… just as it does glucose.”

“As long as your body can use ketones and free fatty acids as ‘food,’ significant amounts of protein won’t be destroyed for glucose production,” Linn wrote. “Your body will use the ketones rather than protein because they are a quite more economical energy supply.” To keep the body from using protein, dieters had to subsist on a supplement that Linn said was “composed of all the amino acids needed to form a protein molecule” that are “present in the usable proportions necessary for this manufacture,” and with the supplement, any muscle broken down would be “replaced by the protein from the formula.”

Linn claimed dieters would lose seven to 15 pounds in just the first week, a total of 20-25 pounds the first month, the same amount the second month, and 16-18 pounds per month thereafter. “Even people who don’t start off needing to lose many pounds can also expect that spectacular drop in the first month,” he wrote. “Some have hailed it as a breakthrough in the battle against obesity,” wrote the Times.

The protein-replacing supplement was called Prolinn, in Linn’s book, though it quickly spawned imitators. Prolinn, per Linn, had "no carbohydrates or fats and fifteen grams of protein," and "a two-tablespoon portion of Prolinn contains sixty calories.” The Times described these supplements as “enzyme hydrolized [sic] collagen,” made from “fibrous protein collagen that is found in a variety of animal tissues and then converted in laboratories to a vaguely gelatinous liquid.” The idea was that dieters would consume only this supplement, and it would let them lose all their body fat, while the Prolinn would keep them from breaking down their muscle.

By the end of 1977, ten women following a “liquid protein diet” had died, their deaths attributed to heart irregularities; 16 more deaths were suspected to be connected. A spokesman for the FDA called investigating these deaths “a top regulatory priority.” Dr. Robert Linn hit back a few weeks later, calling the accusations “premature.” The director of the CDC testified that he suspected some of the deaths were due to starvation, because the diet provided them with only 300 calories per day. Sure enough, a 1980 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that liquid protein diets were associated with cardiac arrythmias. A 1981 study in the American Journal of Medicine found that the liquid protein diet caused a significant loss of minerals in the body, mostly in the kidneys, in a way that wouldn’t necessarily be detectable through blood tests.

Soon enough, though, the controversy was forgotten. By 1989, the Times was writing about the liquid protein diet again, calling it “the diet of the stars,” even as it mentioned that 60 deaths ended up attributed to it in the '70s. Collagen had been unleashed upon the world, and its wobbling mass wasn't going back into the bottle.

If liquid protein was all it was cracked up to be in Linn’s book, no one should have been hurt. Why did people get sick and die? Part of the issue is that no one could survive on one macronutrient for very long. But it was also because some of what Linn was saying mischaracterized how bodies work. Some of it was also outright lies about what collagen is, beginning a tradition of obfuscation about collagen that continues to this day.

The supplement mentioned, the “enzyme hydrolized collagen,” was and is still made from connective tissue (tendons and ligaments), skin, and bones—basically all the parts leftover once the animal’s been stripped of its meat. But what is collagen, really? It is true that collagen is composed of amino acids, just like all protein. But protein and amino acids and collagen are not all interchangeable, and it’s not as simple as “gather up enough amino acids”, yada yada, “ta-da, protein.”

There are 500 kinds of amino acids in the world, 21 of which human bodies use. Of those 21, we need to get nine of them through our diet: histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine.

To understand what “getting our dietary amino acids can look like,” let’s take a 100-gram serving of chicken breast. How much of each amino acid does it have? Going down that list of the nine essential aminos, 100 grams of chicken breast has:

- 1.22g histidine

- 1.64g isoleucine

- 2.7g leucine

- 3.14g lysine

- 0.85g methionine

- 1.32g phenylalanine

- 1.47g threonine

- 1.18g tryptophan

- 1.7g valine

Chicken has more amino acids we don’t need in our diet, like tyrosine, cysteine, glycine, arginine, and proline. Other meats—pork, beef, etc.—will have slightly different amino acid makeups. Other animal protein sources—eggs, yogurt milk—will be even more different. Vegetable sources—beans, peanuts, almonds—will be different again, but we’ll come back to that in a minute. But chicken is a very good source of essential aminos; it has a lot of a lot of them, in the right proportions, so we can make use of them and turn them into muscle very effectively.

We know collagen is also an animal source of amino acids. But again we ask: What is collagen? Collagen is not as specific as “chicken breast”; depending on whether it’s from beef, pork, chicken, a hoof, a bone, skin, or a ligament, its amino acid profiles will be a little different. Most collagens are mainly composed of the amino acids glycine and proline, or glycine and hydroxyproline. The first thing we are going to notice here is none of these is an essential amino acid.

So how much of the essential amino acids are in collagen, if any? What I find funny is that few collagen supplements provide this information on their nutrition panels. Again, it varies depending on the source.[^1] According to one paper that cites numbers for collagen peptides from a “porcine” (pig) source, each 100g consisted of:

- 0.83g histidine

- 1.58g isoleucine

- 2.46g leucine

- 4.22g lysine

- 1.92g threonine

- 0g tryptophan

- 3.6g valine

(In the study's table, the methionine content is combined with non-essential cysteine, but the total amount is only 0.71g. The phenylalanine content is combined with non-essential tyrosine, and the total is 2.91g. I don’t know why this is, but chalk it up to “collagen researchers,” which we will return to in a minute).

You may notice this only adds up to about 14 grams of essential amino acids. So what is the other 86 grams? It’s other amino acids we don’t need by diet, like glycine, proline, hydroxyproline, alanine, glutamic acid; plus some vitamins and minerals needed to hold the structure of the collagen together. So for every 100 grams of collagen ingested, only 14 of those grams meaningfully contribute any dietary protein our bodies can use.

But not all collagen is made equal. The essential amino acid profile of collagen made just from mammal skin looks like this:

- 0.005g histidine

- .01g isoleucine

- 0.02g leucine

- 0.03g lysine

- 0.01g methionine

- 0.01g phenylalanine

- 0.02g threonine

- 0g tryptophan

- 0.02g valine

That all adds up to less than one gram of essential amino acids that we need, per 100g of collagen, and still with none of the essential amino acid tryptophan. Which type of collagen are you getting in a little jar of collagen supplement, the mammal skin or the pork ligaments? Who can say.

But anyway, both of these versions of collagen share two big problems.

One, they are completely missing tryptophan. There’s a scale we use to measure protein digestibility, which is roughly a stand-in for how well our body can use it, called the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). The PDCAAS scores protein not just on its amino acid content, but the proportions of those aminos to one another. Whey protein or milk gets a perfect 1.0 on this scale, because it has all of the right amino acids, all in proportion to each other; we can use them all up with nothing left over. With no tryptophan, collagen gets a 0 on this scale.

It's like this: imagine you wanted to build a plane, and you had the plane body, engines, landing gear, propellers, all the flying instruments you could ever want, but no wings. With no wings, you have no plane. With no tryptophan, you have no meaningful amount of digestible protein.

The other big problem is, tryptophan aside, collagen’s aminos aren’t well-balanced, either. (This is an exceptionally difficult piece of information to find online; the collagen lobby is very strong at SEO.) If supplemented with tryptophan, collagen can be bumped up to a 0.39 on the PDCAAS scale. This is still lower than oats (0.67), rice (0.62), and wheat bran (0.525)—not foods we normally think of as protein sources, yet they still beat collagen in terms of how much dietary protein we can absorb from them.

Many of the ‘70s collagen supplements, including Prolinn of The Last Chance Diet, had added tryptophan, so they could claim they had “all” the amino acids. Linn wrote in his book that Prolinn was “composed of all the amino acids needed to form a protein molecule”—technically true, but misleading—and that they were “present in the usable proportions necessary for [the creation of a protein molecule].”

Whether the scientific understanding just wasn’t there, or Linn was too dumb to know why this might be wrong, or he did know and was lying through his teeth, is no longer possible to know for sure. But in any case, he was wrong. Even with added tryptophan, remember that the aminos in collagen still aren't present in the right amounts relative to one another to be used effectively in the body (at least, not without consuming a truly off-putting amount of wiggly gelatinous goo).

Now—the PDCAAS score of a protein is not the whole story. When protein sources get into our bodies, they are all broken down into their respective aminos, and can then recombine as our body needs them. The amino acid profile of beans, for instance, are an “incomplete” protein, but they are complemented well by rice. This is why it pays to have a diverse diet, and why “balanced” diets are important, why “cutting out carbs” or other big food groups isn’t as clever as many people think it is. But it also means that not every protein needs to be perfectly complete to be useful.

But collagen is still not a great source of these amino acids because a) it doesn’t have that many of them, that consistently, because different collagens are different, and b) their distribution of different amino acids are difficult to complement. Collagen, for all intents and purposes, is like a much, much worse version of meat. Most other protein sources already have what it has, and there aren’t really any foods we consume normally that just fill in collagen’s weak points and would allow our bodies to make use of what the collagen offers. We’d have to bend over really far backward to make collagen work, when we don’t need to; we could just eat any better source of protein.

Well, that’s all fine. But then why on earth are supplements allowed to print on their labels that collagen is “protein”?

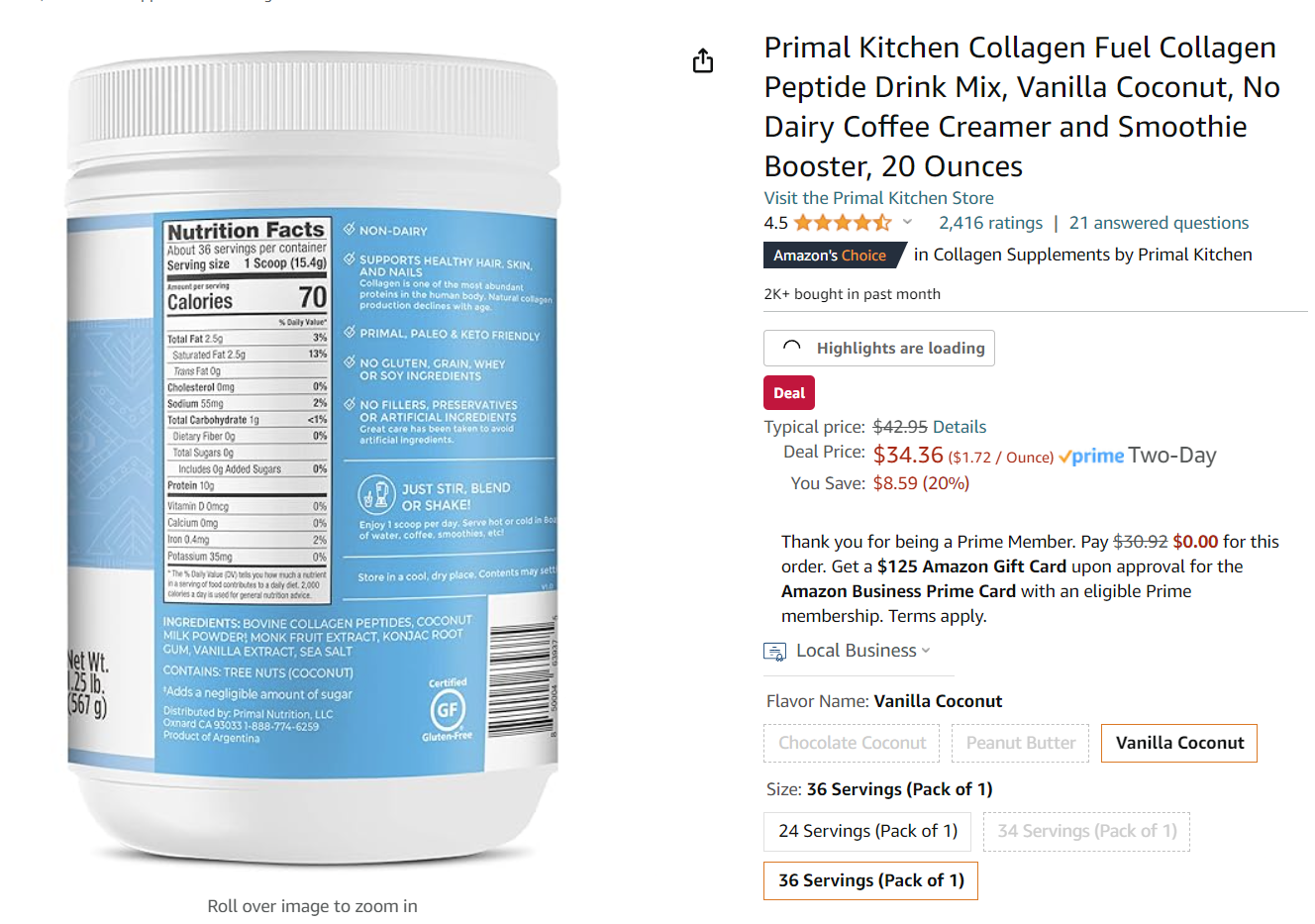

For instance, the label on Primal Kitchen’s Collagen Fuel Collagen Peptide Drink Mix, Vanilla Coconut Flavor says that one serving of collagen is 70 calories and 15.4 grams. The label claims this 15.4 grams contains 10 grams of “protein.” Why doesn’t whoever oversee nutrition labels seem to know or care about this PDCAAS digestibility factor? Why is the label allowed to say a 15-gram scoop of collagen has 10 grams of protein if our bodies won’t even be able to use it effectively?

It’s because nutrition labels just don’t tell us anything about protein quality. The FDA states in its documents, “protein intake is not a public health concern,” and it costs a lot of money to assess PDCAAS. So if a food or product has amino acids, it’s all “protein” in the eyes of the FDA, as long as the product isn’t making claims about how much the protein contributes to a person’s overall needed dietary protein intake. The turning point for whether a product makes this claim is whether it puts a percent-daily-value contribution next to the protein figure. Notice the nutrition label above has no "% Daily Value" figure on its "Protein" line. Yes; this is really the granularity of stuff you have to be aware of in order to suss out bogus nutritional claims.

This is not an issue unique to collagen. For instance, a can of beans will state that it has 7g of protein per serving. But not all of that protein is going to be available to our bodies use, unless its amino acid profile is rounded out by a complementary source, like rice. (This "rounding out" can happen over a matter of days; it does not necessarily have to be within, for instance, the same meal.)

We could argue that the lack of concern about protein quality/bioavailability is an artifact from a time before foods were so highly engineered. But in any case, it’s a loophole that collagen is perfectly primed to take advantage of.

The FDA is saying, essentially, that it has not yet seen enough shenanigans in the realm of protein that require further regulation in terms of assessing digestibility. Taking collagen, or any other bogus protein supplement, is not going to actively hurt anyone in the eyes of the FDA (at least, not because of its weird and mostly unusable amino acid structure). It will waste their time and money, sure. But until someone gets angry enough about that, the FDA is not much of a proactive regulator (but that’s a whole other article).

So, okay, we’ve established that collagen is not really a source of protein, and definitely not a survivable diet unto itself, even for the purposes of short term muscle-sparing fasting. But what about the approximately one million studies and journal publications and newspaper headlines and “nutritionists” and “wellness experts” saying collagen is good for our joints, skin, bones, and so forth? After all, our skin and bones and ligaments and tendons are made of collagen, too. As we get older, our skin gets looser, our joints get stiffer, and our bones get weaker, thanks to a “loss” of collagen. “Natural collagen production declines with age,” helpfully states Primal Kitchen’s Collagen Fuel Collagen Peptide Drink Mix, Vanilla Coconut Flavor, right next to its “10g of protein per serving” nutrition label. Any page of Google results involving the word “collagen” is overrun with collagen salespeople falling over themselves to talk about how amazing collagen is. It seems like a natural conclusion, then, that we should pump our bodies full of collagen—they need it, don’t they?

First, let’s talk about all of these studies in general. I can’t claim to have seen every published scientific study on collagen, but it is an area that is rife with “studies” funded by supplement companies, or conducted by scientists employed by those companies. Those companies are motivated to prove that their product, collagen, isn’t useless. And yes, you are allowed to fund and publish a "scientific" study on your own product that you sell and make money from; no one will stop you, and there is always some journal that will publish it.

Their studies always, conveniently enough, find that collagen is good and effective at making skin bouncier, or making joints hurt less. But the studies often don’t have controls, or are small, or elide significant factors. It’s a mess out there. (A lot of times, what gets cited in news articles or SEO health info sites writing about collagen are “systematic reviews” that don’t cite conflicts of interest or funding, but all of their info comes from a bunch of studies rolled together that are funded or conducted by, you guessed it, supplement companies.)

This all makes it very, very difficult to find out what the deal is with collagen, and what is true and what is marketing bullshit. Unluckily for collagen, I am possessed of a lot of time and have a keen sense of justice.

The thing about all food is that it doesn’t stay in its whole form when it goes into our digestive systems. As noted earlier, all protein is broken down into its respective aminos, which are then reconstituted where they are needed. Our bodies can’t just take the collagen we consume and stick it right where collagen goes in our bodies. Still—what’s so wrong with eating the building blocks of collagen, to try and help our bodies make more collagen?

Two things. The first thing is described well in this Barbell Medicine article, which says, in short, that we can’t dictate where nutrients go once they are in our bodies, or how much or how frequently they get there.

Think of your body’s collagen production process as a mine cart going up a hill that can carry a certain amount of rocks (collagen) each trip. When the mine cart is new, it goes fast, and performs many trips in a day. But as the mine cart gets older, its parts start to rust, and the little old prospector who runs it gets slower at pulling at the levers. As it gets older, it makes fewer and fewer trips per day. The cart develops holes, so it loses some rocks on the way. All this means fewer and fewer rocks get up the hill as the cart gets older. It doesn’t matter how much rock we pile at the bottom of the hill; it will not make the mine cart go any faster or be more efficient. In the same way, pumping your body full of all the collagen you can lay your hands on isn’t going to make your organs spin all those aminos into as much collagen as it was able to when you were 18 years young.

Second—let’s say any of these studies are right, that taking collagen did show an improvement in joint pain or skin bounciness. How could that happen? Well, collagen can be an improvement over nothing at all. For someone who eats only, say, three bowls of dry cereal a day: Of course supplementing collagen will seem to help with their joints or skin. They were getting almost no protein before. Even the little bit of the aminos in collagen are going to be better than the almost none aminos they were getting before.

But these studies rarely control for this kind of scenario. The collagen pushers are always conveniently forgetting to mention that the collagen-protein relationship is kind of one-directional, in a positive way: While dietary collagen is a terrible source of protein, it’s relatively simple and easy to construct body collagen from most proteins, which means that virtually any protein we eat will probably help us regain or maintain body collagen. Just having a sufficient protein intake means your body will be able to make all the collagen it is able to. And per the protein digestibility factor, virtually any protein source, any semblance of a balanced diet, is going to help you do this better than consuming collagen itself.

For people who are eating enough protein, a collagen supplement is a putting a hat on a hat. It’s even more than that—it’s the tiniest, microscopic little bedazzled fez on top of an Indiana Jones fedora. There is no time or money that could be spent on taking collagen that couldn’t be better spent eating or taking virtually any source of more complete protein (which is… basically all sources of protein, and even non-canonical protein foods like rice and bread). Actual protein sources, meat and non-meat, have everything that collagen has, plus more things that it doesn’t that we need.

So then, why, why, why is everyone so amped on collagen?

Because it’s cheap. It’s literally akin to a waste product, the last thing left over after all the other value has been extracted from animals. It is, in effect, meat garbage. It’s like a wood shop selling the sawdust off of its floor. There is a lot of it, just as a fact of how the rest of the protein production machine goes. It’s so cheap to get and make that a lot of money can be spent dressing it up like a fancy self-care moment, a bone broth or an expensive-looking gel, and putting it in the hands of very famous celebrities, and the seller still comes out ahead. (It’s precisely the fact that it requires so much song and dance to sell that should tip us off to what garbage it is.) I'm guessing that it's the magic triangle of "collagen is present in bodies/we lose it as we grow older/we are desperate not to age" that keeps collagen, well, vibrant in the market. The global collagen market is 9.12 billion dollars, and by god, is it growing.

It’s unlikely collagen will ever be marketed again the way it was in 1976, as a whole-diet replacement. For that reason, it’s unlikely to kill again. But it started off its life in the supplement world wildly underdelivering, has never gotten better, and will probably continue to underwhelm and disappoint for the remainder of my days.

Sources

A Food Labeling Guide, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration, 2013

Protein digestibility of cereal products, Foods, 2019

Amino acid content of 6oz of chicken breast, MyFoodData

Collagen Protein and Tendinopathy, Barbell Medicine

The Liquid Diet Protein Controversy, NY Times, 1977

Member discussion