exploring the dead-end forest

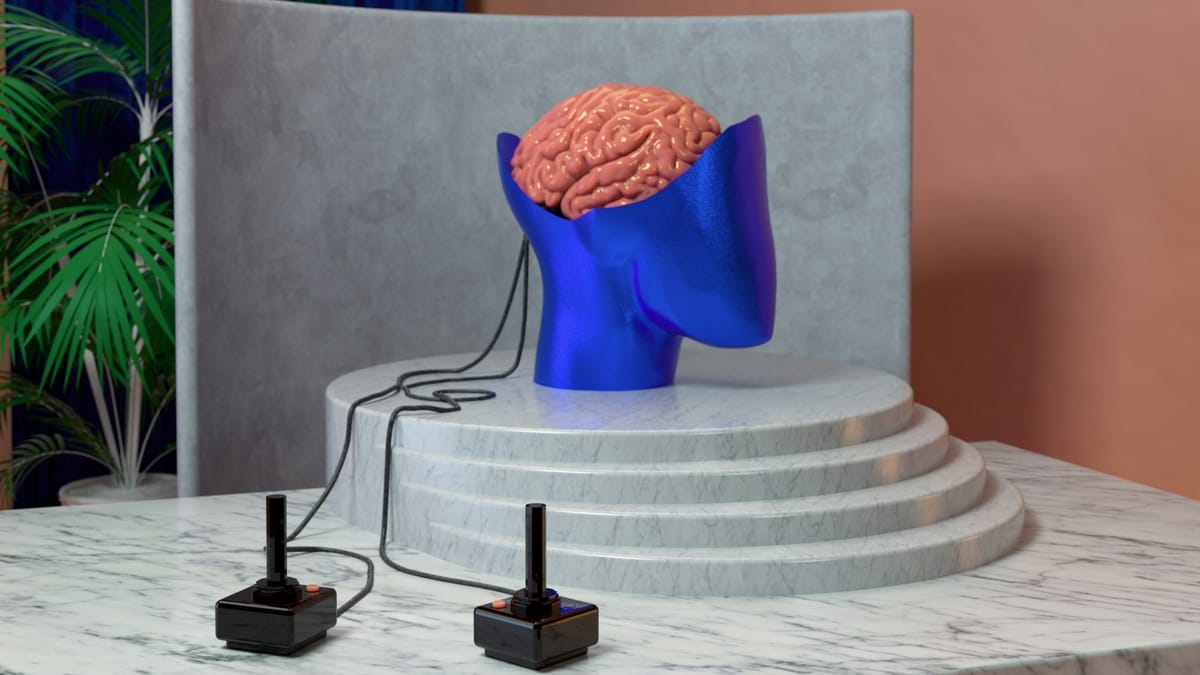

ASK A SWOLE WOMAN

This is the paid Sunday Ask A Swole Woman edition of She’s a Beast, a newsletter about being strong mentally/emotionally/physically.

The next few advice newsletters will feature some of the questions I was asked at this summer of book tour events for A Physical Education. The questions are paraphrased, and some will be mash-ups of multiple similar questions I was asked.

The Question

What am I supposed to do when I get bored with lifting?

The Answer

I grew up in a house at the actual dead-end of a dead end street. I have described this before. It was also at the bottom of a hill, and since there were never any cars coming, my three siblings and I would launch—and I mean launch—ourselves down that hill on every set of wheels we could get our hands on. Bikes. Skateboards. Scooters. That red Little Tikes Cozy Coupe car, with a kid dangling from each side and another on the roof and one inside to steer. Those little square wheeled boards they gave you in gym class with which to run people’s hands over. That we are alive today is an affront to God.

I have a feeling that not many people have looked that closely at many dead end streets, the exact structure and mechanics of them. Most people don’t even go down them, and if you happen to do so by accident, you almost certainly want to immediately turn around and exit the way you came. But in my first eleven years, I got a very good look. There are many kinds of dead ends, but this was ours.

The paved road faded into sand, shallow and scattered at first and then deep—as good as a landing gets when you are reliably coming at it going 20 miles per hour. The sand then gave way to plants, small creeping ones on the ground, and then tangles of native bushes, and then trees that got bigger and bigger the deeper we went. Our wheeled vehicles were mostly useless here. The ground was loose dirt and dry pine needles. Our speed was limited to how fast we could go on foot. But the dead-end forest had new terrain—trees and rocks to climb. Puff mushrooms to stomp. Pinecones to gather.

When the audience member asked me the question above, I asked her what she does that she enjoys. She said hiking. I said do you get bored of hiking? What do you do? And she said I dunno, there are always more places to hike.

This was in Portland, so I don’t know how many places there are to hike there. But in my experience, even in extremely hike-y places, there are maybe 20 hikes[^1] within a half-hour drive time. More, obviously, if you drive farther. And of course hiking a hike in the summer vs. the winter the winter vs. the fall vs. in the rain vs. when it’s dry will be different. But I felt surprised that she did not at all see the potential for boredom with hiking the way she does with lifting. We are nothing if not two specks drifting in the ether of the universe whose paths briefly crossed.

But here is what I want to unpack: when you get bored in the gym, your patience and tolerance has lapped your desire for mastery of whatever you’re currently doing. That means it is time to find something new to do. You are bored of doing the obvious thing, flying down the hill in your red Little Tikes Cozy Coupe; that’s fine, everything gets old after a while. Now it is time to look deeper into the woods at the precipice of which you have been launching yourself over and over, to “go exploring” in the immortal words of Calvin and Hobbes.

It may sound like I’m saying “you need a new goal,” which is not quite it (though that can help, and I’ve advocated for it elsewhere). Part of this is about not putting too much pressure on yourself about maximizing, always getting results. The wonderful thing here is that you have now built some skills that you can bring into a new area, skills you can experiment with and get now get to know in different ways and in new contexts.[^2] In fact, the moment you have some skills is the time to learn to get a little silly with it.

As someone else rudely pointed out, I have a relationship to experimenting with working out that not everyone does. I think it’s fun. But that is the bigger point, which is to consider what might give you a more lighthearted, personal, joyful connection to all this that is not necessarily goal-oriented, that embraces nonlinearity. You have to go into the forest and pick up some pine cones, with an openness to the possibility that you may get bored with the pine cones and need to find a tree to climb.

Unfortunately, I cannot tell you exactly what you will find fun; my idea of fun is not the same as everyone else’s. I was very goal-oriented in lifting for a lot of my early years. But in the last few, I’m doing a lot more sating of my curiosity, trying different things. I haven’t pursued actually getting stronger in a long time.

The foremost goal of my lifting, honestly, is helping me sleep better. The secondary goal for a while has been more like postpartum rehab than anything. But beyond that, I really like trying new accessories that are programmed in RISE, which I am still subscribed to. I like thinking about what stuff I now do with my body more now that I have a baby—standing up with no hands, for instance, or bending down while holding something, or crawling around on the floor. I plan to bicycle him around a lot. The baby has also been bringing me into an increasing number of playgrounds, where I can’t swear I won’t climb every jungle gym. I have a lot of fun stuff I want to do, and the primary purpose of lifting is to help me do it.

Was there anything you liked about what you were doing? Upper body stuff? Single-leg movements? You could look up every single-leg accessory and try them all. Is there anything that feels particularly good, pays off in real life? It could be just hanging from a pull-up bar (great for the shoulders and spine). Maybe you’d like to get back to climbing trees, or be able to throw a child in the air. Working backwards from your life and how you envision it can be a great way to orient yourself, versus chasing the dragon of getting stronger and stronger and stronger.

If you don’t know a lot about what is possible with lifting, it can be hard to imagine new stuff to do for yourself. So it may take a little wandering around to find something you like. You can go into your gym with the goal of only using new machines you’ve never tried before, or take a class you’d never otherwise take. But you have to put yourself in the space of finding new stuff to do, just like you’d log on to AllTrails, or whatever, and browse new hikes, or log onto ClassPass and browse classes.

You can also take such a program and tweak it in small ways to suit your tastes or interests. This can sometimes get in the way of promised results, but is not illegal. This is sort of like when you copy a piece of art in your own hand or retype a manuscript. Paying attention to how programs are put together can give you a greater appreciation of how lifting works, and can be the beginning of fostering a more specific taste. A lifting palate, if you will.

So where does one go to find new things to do? These are some ways and means I have drawn programming inspiration over the years:

- The massive “exercise library” of exrx.net. If you’ve ever been curious what accessories do what, this one is organized by body part, and clicking on a body part will give you a list of exercises that work that part or those muscles.

- One of the first resources I ever found was this reddit Compendium to Overcoming Weak Points. I think it’s still pretty sold.

- Intermediate programs. There are lots of free ones, and some subscription ones that I like.

- StrongerByScience free templates and GZCL. GZCL was how I started to learn about programming in earnest.

- LiftVault has approximately nine million programs that you can pare down to your taste.

- Try lifting programs for other sports. I admit, sometimes I hate these and find them poorly designed, and am a pretty staunch believer in the idea that virtually everyone who does a sport and is looking to integrate some strength training should build their strength base first with a beginner program, before leaning into more sport-specific movements. But if you already have your strength base and have another sport you enjoy, a sport-specific program can be a great way to marry your two interests. There are too many sports for me to make recs, but Google “[your sport] + strength training”. Here’s one for runners from Runner’s World.

Progress can be an awesome and psychologically important feedback loop for a lot of reasons. At one point in my life, I found it helpful and grounding just because it was stable and predictable when a lot of other things weren’t. I think that experience could be helpful to a lot of people who are used to thinking of physical activity, their bodies, and food as unpredictable, untrustworthy enemies. But then there is a second phase, too: I’m finding I can enjoy exploring and experimenting so much more when I’m standing on solid ground, as opposed to shifting sands.