On being 'addicted' to exercise

A couple of months ago I read this wonderful piece from my Hairpin OG Edith Zimmerman, reflecting on whether she was addicted to running. I read it with interest for two reasons: One, “addiction” is a label that people simply love to throw around when it comes to health-related behaviors (though sometimes for valid reasons!). Two, because I’d always meant to sort out the addiction x exercise relationship for myself and had never quite gotten around to it.[^1]

This conversation often comes up when it seems like a person is supplanting a formerly “unhealthy” addiction (gambling, smoking, recreational pedestrian highway crossing, never throwing out any piece of paper in case you might need it someday) with a “healthy” or at least more innocuous one (running, rock climbing, cooking/baking, bird watching). The casual line of thinking often goes something like, “at least what they’re doing isn’t harmful.”

Many would agree that someone who has replaced their recreational pedestrian highway crossing with bird watching is probably overall taking better care of themselves and ensuring a longer life. But if they haven’t slept in three days for want of planning a trip to finally catch a glimpse of the rare East Austrian guttersnipe; if they miss all their children’s soccer games because they broke both legs free-climbing a 40-foot tree to see inside the nest of a high-chested neon warbler; if they are $30,000 in debt because they gave it to the only avian preserve that nurtures the only two remaining creeping toucalans (an ortolan-toucan hybrid with tiny vestigial long-fingered hands) in the lower 48 states? Well.

The concept of exercise addiction is complicated by the fact that exercise is also just one of the things people are predisposed to do, and can’t entirely avoid if we’re not basically in a coma, similar to eating or interacting with other people. The habit-ness of it, which would normally be a flag, is just endemic to our relationship with exercise. This differentiates it from, for instance, other non-substance addictions like internet addiction or sports gambling.

Wanting to reach a certain intensity or time involvement could also be considered a sign in a lot of addiction circumstances. But in the case of exercise, wanting a certain amount of exercise isn’t itself a sign of addiction. You wouldn’t say a dog is “addicted to exercise” just because it’s still hyper when its only physical activity is being walked from the door to the curb to pee, and then back inside.

The major indicators of addiction are what happens when the addictive behavior doesn’t or can’t happen. There are three big ones relevant to this situation: The person desires to stop but can’t; they are preoccupied with it and thinking about it when not doing it; and they experience what psychologists call “negative consequences” as a result of their involvement in it. For exercise, this could be lack of sleep, worsened health, or interference with work/family/relationships. Someone who, for instance, cannot enjoy a vacation because it interferes with their exercise schedule, or cannot give up one three-hour workout a week to go on a date with their girlfriend, maybe doesn’t have the best relationship with exercise. However, someone who can’t sleep well if they don’t get exercise? Green flag.

These things are in the details. Someone who exercises a lot, consistently, and makes it a big part of their life is not addicted per se. But it is possible to have a damaging relationship with an otherwise harmless activity. It is also possible to have a functional addiction to exercise, as with everything else.

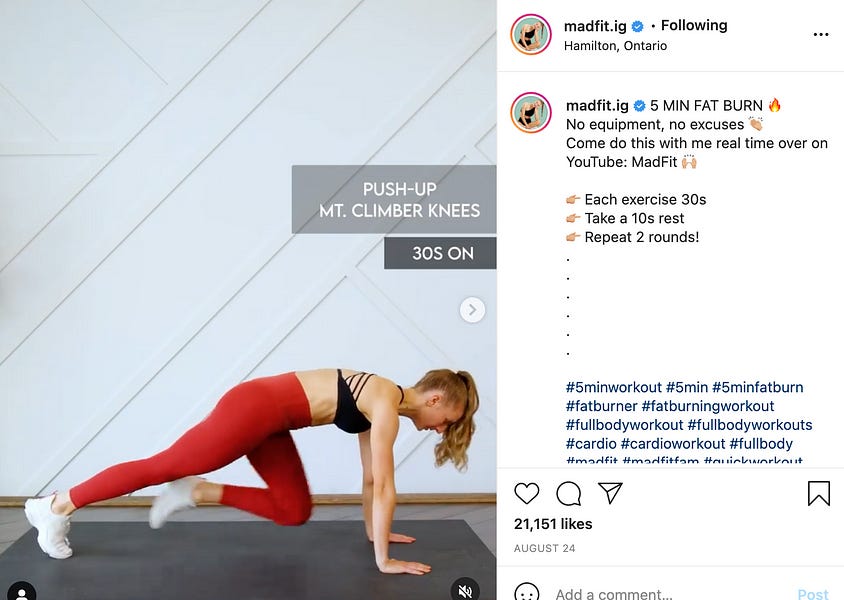

Writing A Physical Education led me to revisit my own relationship with exercise, both when I was still a runner and after I got into lifting. When I was a runner, no question—I felt overwhelming guilt and preoccupation when, for instance, a rainy day meant I couldn’t run.

I did confusingly frame this to other people, and even myself, as “just really liking running.” But I was young and immature. I did not want to cop to having any problems (and if I did, I certainly didn’t want to talk to anyone about them).

And, to be honest, I did not have a very well-rounded understanding of what it meant to “like” anything. Running gave me a sense of control, which I sorely lacked for reasons that are too many and too complicated to get in here (that’s what books are for). I enjoyed feeling that modicum of control; running was more or less the only way I felt any control. One of the reasons I find these situations so interesting is that, even if anyone had managed to rope me into an honest conversation about running, even if they could have led me toward this understanding, I would still have clung to running like the mast of a ship in a hurricane.

Lifting was more complicated. I’ve written before about coming to lifting for only problematic reasons (wanting to be hot, wanting to do something that was easier and less involved than running that would still allow me to be hot). There were surely times early on when I felt tense about having to miss a workout, about not being able to progress my weights like I felt I “should,” about losing progress when I’d have to take time off for such indulgent reasons as “being too sick to get out of bed.” There were many things inside and outside of lifting that had to happen to help me realize that my survival on earth did not depend on exercising, lifting, or running. But lifting did also help in concrete ways: Eating more had the effect of making me literally, biologically less crazed, for instance.

It feels like, as a culture, we can fixate on trying to concretely assess whether people are Addicted to things (and, on a meta level, who is allowed to make those assessments and when). But looking back on my experience, identifying the addiction was the easy part. Even if I didn’t readily admit it, some part of me knew something was wrong, or else I would not have been as defensive and shut-down about it as I was. Trying to find my way back up the storm drain was a much, much more difficult, longer, and non-linear process. I don’t think I did it the rightest or shortest way. But even if “whether” is the first step, it was only a tiny piece.

[F1] To be clear, none of this is meant to be a referendum on whether Edith herself is “correct” or not; her situation is her own, and every situation is many-layered and -faceted.

Member discussion